October 23, 2005

Corn farming in Alfonso Lista, Ifugao

Implications

of promoting market-oriented production

Last of 3 parts

By FERNANDO BAGYAN and LULU GIMENEZ

High Impact on Agro-input Utilization and Credit Assistance Patterns

All corn-producing peasants in Alfonso Lista grow high-input varieties because they find these more productive and marketable. Some are GMOs, but the majority is simple hybrids.

The peasants of Alfonso Lista were introduced to genetically engineered varieties of corn by agricultural input suppliers in Isabela who had entered into dealership contracts with the corporations that had developed these; the promotions personnel of those corporations; and the agricultural officers of government.

Bt corn was brought to Isabela by Monsanto. This was during the field trials the company conducted in the year 2000. In 2003, Monsanto’s Dekalb Yieldgard (DK 818 YG) reached Alfonso Lista.

However, two years since, Bt corn has yet to become the area’s seed choice. Farm operators choose it only when they are late in starting their crop. Thus the crop is more vulnerable to weather problems and pests than if it had been planted on time. They do so because they have observed that Bt corn is more resistant to drought and corn borers, compared to the terminators and simple hybrids; also, rats avoid it.

As much as possible, the peasants of Alfonso Lista steer clear of Bt corn because they have experienced severe itching when handling the plants during crop care and threshing; also when handling the corn grain during shelling and drying. In addition, they have heard reports from fellow corn producers that there have been cases in Lamut, Ifugao that carabaos died after eating the vegetative parts of the corn. Cattle’s hooves are cut when trampling corn stubbles in newly harvested fields.

An additional consideration is that the seeds of DK 818 YG cost about twice as much as other corn seeds (P4,650 vs. P2,300 to P2,800 per 18-kilogram sack). The herbicides required in the crop care are also much expensive (P1,350 vs. P250 to P900 per 1-liter bottle). [The Bacillus thuringensis in Bt corn transfers to any weeds surrounding the corn plots and makes these weeds just as sturdy as the corn crop. Thus, there is the necessity of applying a very powerful herbicide specifically formulated to kill “Bt weeds”.]

The peasants of Alfonso Lista are not yet aware of the findings that the Bacillus thuringensis protein in Bt corn can be transferred to other plants in the farm environment – including any food crops that they grow near their corn fields for their own households’ consumption. They are neither aware of the findings that the antibiotic markers that allowed the Bacillus thuringensis protein spliced into corn DNA can significantly reduce the ability of both people and livestock consuming corn grain to make use of antibiotics like Streptomycin. Possibly, if they are aware of the aforesaid findings, the peasants of Alfonso Lista will become even less receptive to Bt corn – not withstanding the aggressive promotion of this GMO by their agricultural input suppliers, Monsanto, and government.

The seed of choice is Syngenta’s NK 5447, a hybrid with a longer cob and more kernels.

On the average, the corn producers use about eight cavans (400 kilograms) of fertilizer per hectare for a relatively new field. Fields that have been in use for several years require larger amounts. Some cornfields require an average of twelve to fourteen cavans (600 to 700 kilograms) of fertilizer. Fertilizer costs P740 to P970 per cavan.

The corn producers utilize herbicides quite heavily because they find this more economical than hiring extra-household labor. It would take ten persons to weed one hectare of cornfield for one day. Wages and food for 10 persons would cost up to P1,700. Herbicides would do the job for a minimum of P250 to a maximum of P1,350.

Most of the corn-producing peasants of Alfonso Lista lack money to spend on the inputs they need; thus, they avail of credit. However, there are no functional credit institutions within the municipality. Both government and private agencies have tried to establish cooperatives here, but all the co-ops they started have gone bankrupt because of mismanagement.

Some of the peasants get credit from the Santiago branch (Isabela) of Quedancor, the Quedan and Rural Credit Guarantee Corporation affiliated with the DA, but has been re-organized and placed directly under Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo’s (GMA) office. Its main function is to provide credit for endeavors in line with GMA’s agricultural modernization priorities.

Quedan borrowers need to have a group of at least three individuals. Collateral is required – usually in the form of land property. The loan is in the form of seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides. It matures within six months, at an interest rate of 1.5% monthly.

Unwillingness to surrender any collateral, or lack of people composition joining a Quedan group, the majority of Alfonso Lista’s peasants just enter a credit supplying arrangement with one of Santiago’s agricultural input dealers. The creditor arranges all the necessary inputs at an interest of 30% for one cropping, and the debtor is obliged to sell his or her crop to the creditor even if other dealers offer higher prices. No collateral is required. But reneging on the terms of the loan will have dire consequences. The debtor will be blacklisted by the creditor and lose access to future loans – unless the debtor’s inability to deliver his or her harvest and payment of the loan is due to crop failure. In this case, the payment of the loan will simply have to be made at the next harvest, but at double interest. In the meantime, the debtor will have to take out another loan to produce the next crop that he or she must deliver.

Produce Buying and Pricing

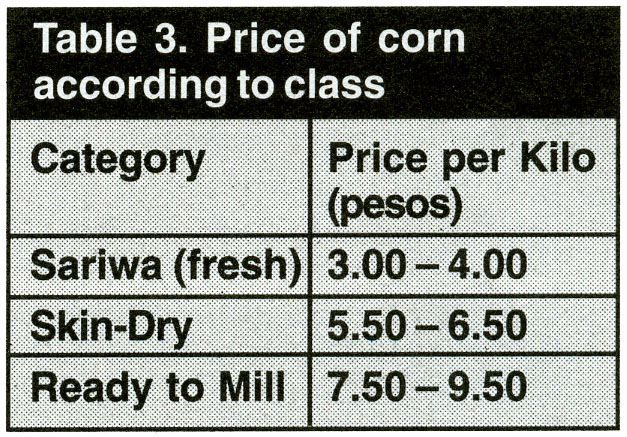

The dealers classify the corn they receive according to appearance and moisture content, and they pay a different price for each category. Freshly harvested corn is classified as sariwa; corn that has been sun-dried for a few days is classified as skin-dry; corn that has been dried completely is classified as ready-to-mill. Each category is further sub-categorized into Class A, B, and C, depending on grain quality. See table 3.

No instruments are used to accurately measure moisture content and grain quality. The dealer simply scoops up a handful of corn grain, classifies it by sight, and quotes the corresponding price. Cases of under-classification are thus common.

Many of Alfonso Lista’s peasants feel that beyond the matter of moisture content – which naturally affects weight – classification is quite unnecessary. No matter the variations in grain quality, all the corn is mixed together when milled.

There has not been much variation in the price matrix for the last five years. The probability of a higher price is very remote (undue of the inelastic corn demand) because of today’s many corn supply sources, given the liberalization of agricultural imports.

In fact, it often happens that the corn market gets temporarily flooded. Then grain dealers proclaim a halt to their buying. At such times, the peasants of Alfonso Lista are forced to store their corn, affecting grain quality.

The Role of Government

As indicated previously, government has played a key role in promoting modern corn breeds among the peasants of Alfonso Lista. This role has not been limited to the use of persuasive words. The Municipal Agricultural Office (MAO)- Alfonso Lista has also been conducting field trials and technology demonstrations using different corn seeds provided free by the agricultural input-producing firms like Monsanto (through its Philippine research partner, Ayala), Syngenta, Pioneer, Corn World, BioSeed, and Asian Hybrid. In addition, the MAO has been selling these firms’ corn seeds to first-time users among Alfono Lista’s peasants at a subsidy, for only half the prevailing market price. Like this subsidy, the credit facility (through Quedancor) available to crop growers can be viewed as a form of incentive.

Implications

The experiences of corn-producing peasants in Alfonso Lista underscore the seriousness of the implications posed by the Philippine government’s promotion of the market-oriented production of modern plant breeds through its agricultural modernization programs.

1. The modernization is limited to the orientation and technology of production; it does not translate into a progressive transformation of the social arrangements that surround agricultural production and trade, such as those that pertain to input supply, credit, and the sale of the produce.

The programs promote the intensive utilization of inputs that can only be acquired through the expenditure of substantial amounts of money, and they promote this among peasants with little money. To access the inputs, the peasants thus need access to credit. Nowadays, the Philippine government, through Quedancor, offers such credit, but on conditions that include the surrender of collateral in the form of landed property – a condition that peasants coming from indigenous Cordillera cultures find hard to live with.

As in the case study area, if no production credit cooperatives exist to provide an alternative, then the peasants unavoidably turn to moneylenders or to agricultural input dealers with whom they can negotiate credit financing or supplying contracts. Invariably, throughout the Cordillera and the neighboring lowlands, the agricultural input dealers are also agricultural commodities traders. And invariably, their credit financing or supplying contracts oblige their debtors to surrender to them the exclusive rights to sell the crops that are produced using the money or inputs they provide on loan. Perforce, the peasants give up any opportunity they could avail of to earn more money if they were free to sell their crops to others.

But even if they were free to trade in their own produce, peasants would most likely encounter no such opportunity these days. In a market flooded with cheap imports, the prices for their produce have become inelastic. Most likely, they will only earn enough for their households’ subsistence. Most likely, they will again borrow money or inputs for their next harvest.

Season after season of these mires, the peasants engage in a dependency relationship with their creditors – a more feudal and backward relationship rather than modern or progressive in character.

2. Debt is repeatedly incurred, and continually increases as the peasants are caught in a pattern of steadily increasing input utilization.

At first, the use of inputs increases because of the compulsion to earn more than is needed to pay a standing debt. At this point, the increase is simply due to the expansion of the area that has been used to grow the new crop. More and more lands are converted to the production of this crop. Then problems emerge from the imbalance that now obtains in the farm ecosystem. Problems have also emerged from continuous cultivation of the land to a single crop. At this point, increasing utilization of inputs has been necessitated by growing problems in soil degradation and pest infestation.

3. It has not yet happened in Alfonso Lista, but other parts of the Cordillera where the adoption of modern plant breeds for market-oriented production has given rise to monocropping, heavy input utilization, and dependency on credit for agricultural inputs. Peasants have also become dependent on crediting the most basic subsistence goods. This is particularly true along the Vegetable Belt- from La Trinidad, Benguet northward to Bauko, Mountain Province and eastward to Tinoc, Ifugao.

Like credit for inputs, the agricultural inputs and commodities dealers- whom are wholesalers also extend credit for subsistence goods or retailers of rice, dried fish, and processed foods. It is necessitated by incidences of crop failure and negative performance in the market. It shows up the risks that peasants face when they give up producing food for their own consumption and abandon the diversified cropping system traditional to peasant agriculture. #