October 23, 2005

Corn farming in Alfonso Lista, Ifugao

Implications

of promoting market-oriented production

Part 2 of 3

By FERNANDO BAGYAN and LULU GIMENEZ

The Introduction of Modern Plant Breeds Starting with the Green Revolution

At the start of the Green Revolution in the 1970s, the first modern crops introduced in the municipality were rice breeds developed by the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI). The Marcos government through Masagana 99 (Abundance) vigorously promoted these. IR-8, the first variety developed by IRRI, and succeeding varietal lines immediately gained entry into the municipality due to its nearness to Isabela - Masagana 99’s prime target area.

Rice producers were enticed with the promise of higher yields at shorter cropping periods and a credit offer for their first package of rice seeds, fertilizer, and pesticides. In a very short span of time, the seeds of Intan, several kinds of glutinous rice, C-4, Wagwag, and others vanished from most parts of Alfonso Lista; only a few peasants in the more remote barangays still planted these traditional rice varieties. In that same span of time, fertilizer and pesticide use proliferated.

Towards 1980, the Marcos government built the Magat Multipurpose Dam in Isabela and (in 1981) brought some of the irrigation to Alfonso Lista as part of its promotion of the Green Revolution technology package. Rice hectarage in Alfonso Lista increased dramatically because of this. Land previously used to growing a diversity of food crops was converted to the monocropping of IRRI rice.

More recently, varieties developed by the Philippine Rice Research Institute (PRRI) have also gained entry. The production of these varieties requires the same technology as that of the IRRI varieties.

Other modern plant breeds introduced to the area were those of vegetables and tobacco.

In the late 1970s, the Ibaloy and Kankanaey coming from Benguet, where the Mountain State Agricultural College (now Benguet State University) was promoting high-input farming, brought in Green Revolution seeds of temperate-clime vegetables. At first though, only a limited amount of chemical fertilizer had to be used in the vegetable plots of Alfonso Lista because the soil here was still very rich. But more fertilizer and large amounts of pesticide had to be used after several years of monocropping. Input utilization has since steadily and continually increased, as the inputs themselves ruined the balance of minerals in the soil and among organisms in the farm environment.

Although not indigenous to the country, tobacco (grown in Northern Luzon since the 18th century) has become a traditional part of farming systems in the Cordillera, as well as the Cagayan Valley and the Ilocos regions. However, the tobacco now grown in Alfonso Lista is no longer derived from traditional seeds. It is a high-input breed of Virginia tobacco that was also introduced here during the 1970s, as part of the overall program of the Green Revolution

In Alfonso Lista, only bananas are still grown using traditional planting materials and technology.

The Popularization of Modern Corn Breeds

Modern corn breeds spread to Alfonso Lista from Isabela, where agriculture authorities promoted them in a series of campaigns trying to replicate Masagana 99’s success. These included Maisan (Corn Country) 77, the Ramos government’s Medium Term Agricultural Development Program, the Estrada government’s Agrikulturang Makamasa (Agriculture for the Masses), and most recently, GMA’s Ginintuang Masaganang Ani (Golden Harvest of Plenty). The breeds that first gained entry were the public varieties developed by the University of the Philippines Institute of Plant Breeding. But these were soon overtaken by varieties privately developed – specifically those of San Miguel Corporation, Corn World, Pioneer Hy-Brid, East-West, Cargill, Monsanto, and Syngenta. With the seeds came the chemicals purposedly designed for them.

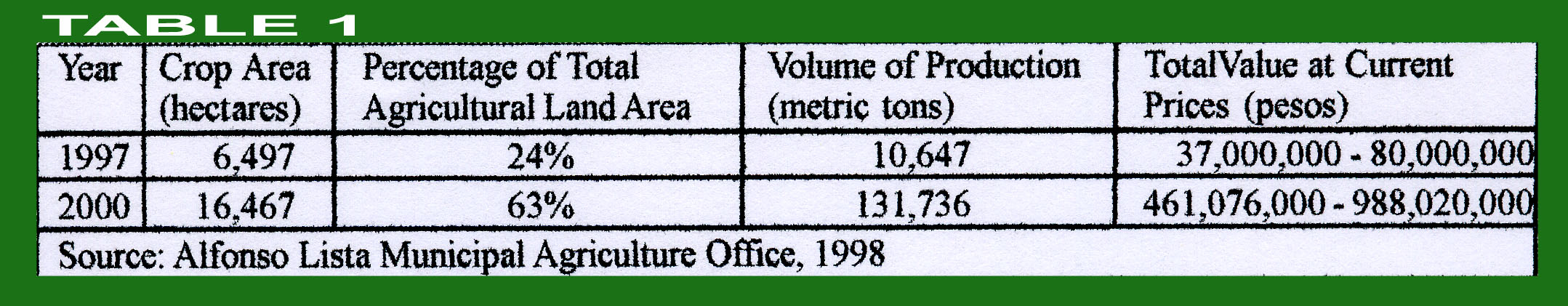

Since 1997, monocrop production of corn has increased dramatically. Over a span of just four years (1997-2000), the area devoted to corn expanded by 253%, and production volume rose by more than 1,000%. (See Table 1)

The impetus for this came from a high market demand for corn generated by the establishment of numerous animal feed mills in Northern, Central, and Southern Luzon.

Most of the corn produced is yellow corn. The peasants of Alfonso Lista devote only a few small plots to the production of white corn for their own households’ consumption and local trade.

Low Impact on Land Holding and Tool Ownership Patterns

The use of high-input varieties in Alfonso Lista has not significantly altered the traditional peasant pattern of land tenure in the area: almost all households here still own most of the land they till. The enforcement of the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Law in the area resulted in the subdivision of the old homestead patents, covering at least 24 hectares each. But in most cases, this was simply a matter of formalizing the de facto subdivision of the patented landholdings among the original homesteaders’ heirs.

Only in a few cases these heirs have been compelled to sell land, to pay debts incurred with agricultural input and commodities dealers. But no single buyer accumulated land from such sales. In all cases, one peasant sold the land to another within the same settlement.

The majority of landholdings planted to corn ranges from one-half to three hectares in size. Some households with less than a hectare rent additional land from those with larger holdings.

In very few cases, land that has already been subdivided among a homesteader’s heirs is still operated by those heirs as a single farm, under a single manager. Farms of this type are ten hectares or larger, and the operations here involve more modern implements of production.

In general, implements still include the simple plow, harrow, and carabao, and traditional handheld tools. But some modern mechanical equipment have entered the scene: small tractors and row planters, backpacked sprayers, threshers and shellers.

Households still own almost all of the implements they use. The exceptions are with threshers and shellers: some households have not been able to acquire these and so rent them from neighbors who have.

Most households do not have their own vehicles to use for transporting their produce. They thus hire truckers, paying them at a rate of P 1.00 per kilo transported. The dealers to whom the corn will be delivered own some of the trucks. The dealers use these same trucks to transport the corn to feed millers.

Next week: Agro-input utilization and credit assistance patterns